PAKISTAN

By Ramesh Raja

Karachi was once envisioned and briefly lived up to its reputation as a modern, orderly, and cosmopolitan city. Before the 1960s, it functioned as a planned urban center with strong municipal governance, functional infrastructure, and a visible sense of civic responsibility. This transformation was not accidental; it was the result of visionary leadership, organized civic institutions, and communities that believed in building and protecting public assets. Wide roads, efficient public services, disciplined neighborhoods, and respect for public space defined the city’s character. Today, despite massive investments in infrastructure, Karachi stands far removed from that vision.

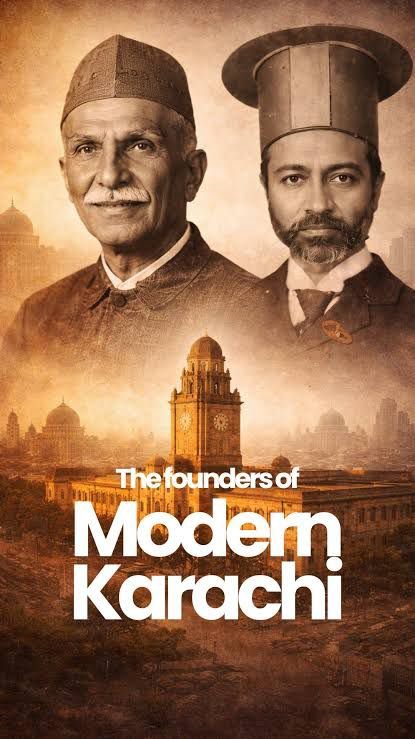

A key architect of Karachi’s early modernization was Seth Harchandrai Vishandas (1862–1928), widely recognized as the Father of Modern Karachi. Serving as mayor from 1911 to 1921, he transformed Karachi from a modest town into a functioning modern city. Under his leadership, electricity was introduced in 1913, gas lamps illuminated the streets, footpaths were laid, and major arteries, such as Bunder Road, were upgraded. As a central figure in the Karachi Municipal Committee, Harchandrai Vishandas studied international city laws and implemented cleaner, more organized systems of civic planning; principles that today’s Karachi sorely lacks.

Alongside him, the Parsi community played an indispensable role in the city’s civic and infrastructural development. Their contributions to municipal services, urban discipline, philanthropy, and institutional governance helped Karachi emerge as one of the best-managed cities in the region. Jamshed Nusserwanji Mehta, Karachi’s first elected mayor (1933–1940), is remembered as the visionary civic leader who laid the foundations of the city’s modern, inclusive municipal governance.

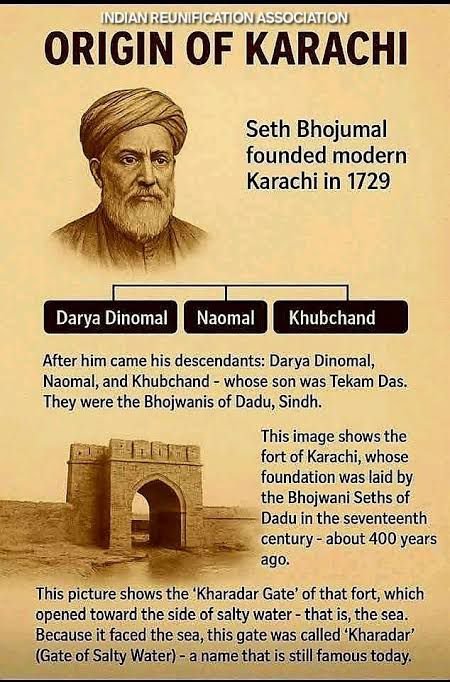

Seth Bhojumal, another early pioneer, was instrumental in the city’s foundational growth, while developers such as Hussain-D’Silva Construction Company contributed to early modern infrastructure, including the construction of the first government barracks in 1946.

Historically, Sindhi Hindus were central to establishing and building Karachi. Their legacy remains visible today in old historic buildings, temples, commercial districts, and early infrastructure that once symbolized stability, planning, and civic pride. The modernization of Karachi before the 1960s was therefore a collective achievement rooted in leadership, community participation, and respect for urban systems.

In stark contrast, present-day Karachi offers a different picture. From aerial footage, the city appears impressive. Hundreds of flyovers, underpasses, and multilane roads glitter with decorative lights, fresh paint, and artistic murals. At night, Karachi can look aesthetically pleasing, almost futuristic. Yet this beauty is largely cosmetic.

At ground level, the illusion collapses. Beneath nearly every flyover lies neglect. These structures, built at enormous public cost, have become shelters for drug addicts and informal encampments, while the loops and edges of bridges are routinely used as open garbage dumps. Roads meant to symbolize mobility and progress have turned into channels where waste is casually thrown from high-rise buildings. Public infrastructure exists, but public responsibility does not.

Streetlights are installed without protection or maintenance. Their wiring is stolen, bulbs disappear, and only hollow poles remain mute witnesses to institutional failure. Artistically painted walls, intended to promote culture and civic pride, are quickly defaced with pan stains and litter. This decay is not merely social indiscipline; it reflects the collapse of enforcement, ownership, and urban ethics.

The problem is magnified by the absence of maintenance planning. Billions of rupees are spent on construction, yet almost nothing is allocated for upkeep. Infrastructure is treated as a political showcase rather than a living system. Roads break, drains clog, lights fail and no institution is clearly accountable. Development without maintenance is not progress; it is structured waste.

Equally alarming is Karachi’s failure to implement a comprehensive solid waste management system. In many countries, waste is treated as an economic resource through recycling, energy generation, and organized collection. Karachi, despite its scale, continues to rely on informal and hazardous practices. At a disturbing level, children, often from marginalized Pashtun communities, can be seen collecting recyclable materials from garbage dumps to survive. This is not urban resilience; it is urban abandonment.

Karachi also lacks strong, empowered city institutions comparable to those governing cities such as Singapore or New York. A modern city requires autonomous municipal authority, professional urban planners, transparent revenue systems, and strict enforcement of civic laws. Karachi’s governance remains fragmented across multiple agencies and political interests, rendering it incapable of managing a megacity.

A further structural injustice lies in Karachi’s relationship with the federation. The city generates a substantial portion of Pakistan’s revenue while accommodating millions from across the country. Despite this, it receives disproportionately limited resources for sanitation, housing, transport, and social services. A city that sustains the national economy cannot be allowed to decay under fiscal neglect.

Reviving Karachi as a modern city requires more than flyovers and decorative paint. It demands a return to the principles that once defined it under leaders like Seth Harchandrai Vishandas, Jamshed N Mehta, strong municipal governance, informed civic planning, respect for public assets, and community ownership. Citizens must be educated to protect public spaces, while the state must enforce laws impartially. Maintenance must become as important as construction, and waste must be managed as an economic and environmental priority.

Karachi does not lack history, capacity, or potential. It lacks vision, discipline, and continuity. If the city is to reclaim the spirit it possessed before the 1960s, development must move beyond cosmetic infrastructure toward human-centered urban management. Only then can Karachi transform from a city that looks modern from the sky into one that truly lives and functions as a modern city on the ground.

READ MORE

OGDCL Tests New Gas and Condensate Well at Dars West Field in Sindh

PAKISTAN Oil and Gas Development Company Limited (OGDCL) has successfully tested a new development well…

HBL Reappoints Muhammad Nassir Salim as President & CEO for Two-Year Term

PAKISTAN Habib Bank Limited (HBL) has announced the reappointment of Mr. Muhammad Nassir Salim as…

PC Board Forms Committee to Negotiate with ADB on Islamabad Airport Privatisation

PAKISTAN The Privatisation Commission Board (PC Board), in its 248th meeting held on Monday, constituted…

Govt Imposes Captive Power Levy Under IMF Condition; Financial Benefit to Go to Consumers

PAKISTAN The federal government has reportedly imposed a levy on captive power plants in line…

Fast Cables Limited Completes Plant Expansion Using IPO Proceeds

PAKISTAN Fast Cables Limited has announced the successful completion of a major expansion of plant…

Chemical Manufacturers Raise Sector Concerns; Minister Assures Policy Review

PAKISTAN A delegation of the Pakistan Chemical Manufacturers Association (PCMA) presented its concerns regarding the…